I recently saw a funny blog post titled a “Tech Guy’s Version of the Perfect Cup of Coffee.” It wasn’t meant to be funny, but it wasn’t very knowing. The author buys Peet’s grocery store coffee beans, uses a mediocre grinder, and pours distilled water (from a pot that keeps it hot all day) over one of the Chemex filter drip pots that science geeks used in the ’70s.

When I want drip coffee, I heat reverse osmosis filtered water to the right temperature (201 F) on demand in a digital electric Pino kettle and pour it over a measured pile of grounds in a $15 Clever Coffee Dripper with a nice Filtropa filter in it on a gram scale. The critical part is the coffee, which I roast myself. Peet’s is an over-roasted blend that’s designed for high profitability; the darker you roast, the less caffeine in the cup, so the more coffees you can sell a given person. That’s nice work if you can get it, but any home roaster can do better with a little experience. Most of the coffee I drink is espresso and cappuccino, however.

It all starts with your coffee beans. Every couple of months, I pick up a batch of green coffee beans from Sweet Maria’s, an Oakland coffee importer run by Tom Owen, a man the New Yorker called a “mad scientist” and a member of the “coffee dream team.” His palette is impeccable, as they say, and green beans are well less than half the price of roasted ones.

I roa st a batch once a week or so in a Behmor 1600, an economically priced home roaster with a capacity near a pound, about what I drink in a week.

st a batch once a week or so in a Behmor 1600, an economically priced home roaster with a capacity near a pound, about what I drink in a week.

Once you know what you’re doing, it takes 20 minutes to roast a batch, probably less time than it takes to drop by a good coffee shop for some roasted beans. Roasted coffee doesn’t keep more than about ten days unless you freeze it at -10 F anyway (that’s deep freeze temperature, not freezer in the fridge level) so it’s a weekly chore to top up your inventory for most people anyhow.

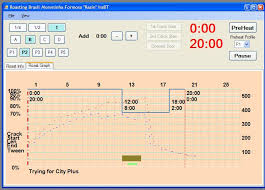

I keep track of my inventory and roast history with a program called “Roaster Thing” developed by a coffee geek named Ira that has an optional USB-connected temperature sensor. One day, Roaster Thing will control the temperature in the Behmor and I’ll be able to create custom roast profiles for each batch (heat curves that squeeze the full flavor out of each batch.) An alternative is the pricier HotTop, but it’s only a half-pound device and isn’t computer-integrated.

I keep track of my inventory and roast history with a program called “Roaster Thing” developed by a coffee geek named Ira that has an optional USB-connected temperature sensor. One day, Roaster Thing will control the temperature in the Behmor and I’ll be able to create custom roast profiles for each batch (heat curves that squeeze the full flavor out of each batch.) An alternative is the pricier HotTop, but it’s only a half-pound device and isn’t computer-integrated.

After the appropriate resting period (three days, usually) I grind in a Bartaza Vario that’s programmed to produce about 18 grams at the touch of a button. Ideally, I’d use the new Vario-W that grinds to precise weight rather than time, but mine is close enough and the Vario-W doesn’t grind directly into the espresso basket anyway. When changing roasts, I check the weight with a $25 gram scale from Amazon.

After the appropriate resting period (three days, usually) I grind in a Bartaza Vario that’s programmed to produce about 18 grams at the touch of a button. Ideally, I’d use the new Vario-W that grinds to precise weight rather than time, but mine is close enough and the Vario-W doesn’t grind directly into the espresso basket anyway. When changing roasts, I check the weight with a $25 gram scale from Amazon.

The Baratzas are kind of messy, so I use a little funnel that keeps most of the grinds in my espresso basket.

Then I pull my shots with a Breville BES900XL Dual Boiler espresso machine. The Breville is the most “tech guy” part of the setup because of the way it was specified and designed. Breville is an Australian company that specializes in smart kitchen appliances, which is to say appliance with embedded microprocessors that make routine kitchen tasks like toasting, juicing, and blending more manageable. Australia, surprisingly enough, is a nation that’s perhaps even more obsessed with espresso than is Italy, and there’s strong competition to serve the market for home espresso machines between Breville and Sunbeam.

Then I pull my shots with a Breville BES900XL Dual Boiler espresso machine. The Breville is the most “tech guy” part of the setup because of the way it was specified and designed. Breville is an Australian company that specializes in smart kitchen appliances, which is to say appliance with embedded microprocessors that make routine kitchen tasks like toasting, juicing, and blending more manageable. Australia, surprisingly enough, is a nation that’s perhaps even more obsessed with espresso than is Italy, and there’s strong competition to serve the market for home espresso machines between Breville and Sunbeam.

Sunbeam raised the bar with a dual pump/dual heater machine that permits espresso brewing and milk steaming at the same time, tricky because they require different temperatures. The Sunbeam produces a decent but not exceptional shot in most hands. It wouldn’t work well in the US because it uses thermoblock heaters than require 230 volt electricity for optimal operation.

Sunbeam raised the bar with a dual pump/dual heater machine that permits espresso brewing and milk steaming at the same time, tricky because they require different temperatures. The Sunbeam produces a decent but not exceptional shot in most hands. It wouldn’t work well in the US because it uses thermoblock heaters than require 230 volt electricity for optimal operation.

Breville did Sunbeam one better by hiring a dream team of coffee geeks and haunting the Internet’s coffee fanatic message forums to find out what the high-end espresso consumer was after. These forums, with names like CoffeeGeek, Home Barrista, and Coffee Snobs, are the places where coffee fanatics exchange tips on everything from beans to hacking their roasters, grinders, and espresso makers for maximum performance.

CoffeeGeek readers figured out how to adapt precise electronic temperature controllers (“proportional integral derivative” controllers or PIDs) to their machines, a practice that produced the first major upgrade to espresso making in 40 years. This is user-driven innovation.

Breville uses two PIDs in the Dual Boiler and borrows techniques from the high-end ($6500) La Marzocco GS/3 espresso maker, such as preheating the brew water with a heat exchange process driven by the higher temperature steam boiler. The Breville also pre-infuses and has the best user interface ever devised for a consumer-grade coffee machine of any type.

If you’re a tech guy and you like coffee, this is your way to a more perfect cup of coffee. The all-in price of a setup like this is close to $2000. That seems like a lot, but consider that your price per double espresso is about 50 cents. Now calculate how long it takes you to pay yourself the two grand back at $2.50 a cup.

And by the way, you’ll be drinking better coffee with as much or as little caffeine as you like; the roasting time and dosing controls the caffeine content, you see, and the flavor is whatever you want it to be.

This is another tech guy’s version of the perfect cup of coffee.

One thought on “How to Make a Cup of Coffee”